In the 1920s, a British chemical manufacturer combined water, mineral oil, and beeswax to produce Brylcreem, a popular hair cream. The product’s jingle — “A little dab will do ya!“ — constantly played on radio and television stations.

Has this slogan, repeated over and over, become the theme song for the Federal Reserve’s long-standing love-hate relationship with inflation? Does their historical approach to it — “take a little dab of inflation to make the American economy increase production and reach full employment” — stand the test of time?

Does higher inflation increase employment?

In 1958, Professor of Economics William Phillips of the London School of Economics wrote a paper titled “The Relation between Unemployment and the Rate of Chance of Money Wage Rates in the United Kingdom, 1861-1957.” He proposed that an inverse relationship existed between employment rates and wage increases in the economy. Simply put, increased employment levels will correlate with higher rates of wage rises. This became known as the Phillips Curve.

Noted American economists Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow embraced the Phillips Curve. Their support of the theory that inflation and employment are linked became the dominant strategy of the Federal Reserve to manage the economy.

Government leaders, economic gurus, and Congress assumed the relationship between inflation and employment was stable, exploitable, and long-term so that permanent low unemployment rates could be “bought” by modestly high inflation rates.

Does higher inflation increase growth?

In the 1950s and 1960s, few economists challenged the theory that a little dab of inflation drives economic growth.

Supposedly, more money in the system encourage more consumer spending and economic growth. Rising wage rates trigger more economic growth and reinforce the inflationary cycle. On January 25, 2012, Fed chairman Ben Bernanke targeted a 2% average for the core inflation rate.

If a dab of inflation drives GDP growth, some economists reasoned that higher inflation would drive higher growth. Economists associated with the Peterson Institute for International Economics, including renowned economist Lawrence Summers, advocate doubling the target inflation rate to 3%–4%,

A side benefit of ongoing inflation is its benefit to debtors. Since the money paid to pay off debt in the future will be less valuable (lower purchasing power), consumers are encouraged to incur debt, which stimulates the economy even more.

This effect is especially attractive when the national government is the biggest debtor in the system. While living standards may rise, the increase is likely due to increased debt, not real wage increases.

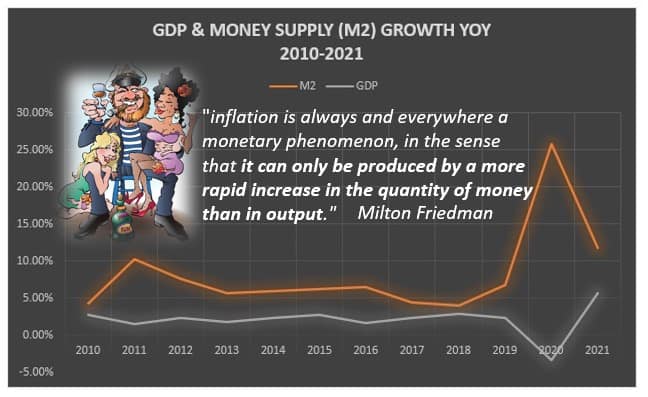

The Fed increases inflation by increasing the money supply. Since 2010, the nation’s money supply growth has significantly exceeded GDP growth.

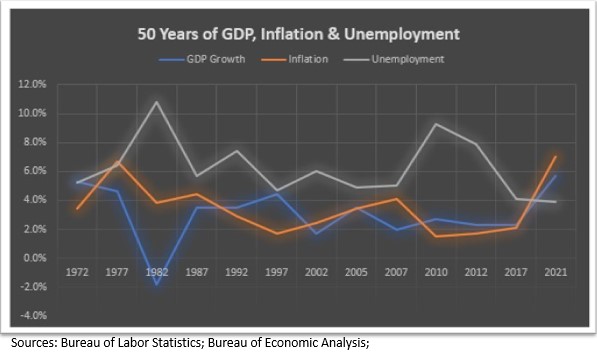

From the early 1990s through 2017, inflation ranged between 2% and 4%. The rate seemed acceptable since the Federal funds rate declined from 8% in 1990 to almost 0% by 2009, and since then it only grew in March 2022 to 0.25%.

On May 4, the Fed raised it another 0.5%, so we are still at an effective rate of under 1% with the inflation rate at 8.5%. The low Fed rate has encouraged borrowing and additional spending to meet the theory of increased GDP growth.

Where’s the growth?

The combination of a slowing economy due to COVID and supply chain disruptions and the open money floodgates of the Fed unleashed the inflation monster in 2021. And with inflation running hot in 2021, the economy grew as it opened back up post-Covid.

However, the first months of 2022 tell a grim story as GDP decreased at an annual rate of 1.4 percent in the first quarter of 2022. This throws some doubts into the Fed premise that higher inflation supports growth. We don’t have growth, but we have inflation.

The Fed ignores warnings about rising inflation

Despite economists’ warning about the danger of rising inflation, the Fed showed little concern in early 2021, focusing on employment:

- “The kind of troubling inflation that people like me grew up with seems far away and unlikely.” – Fed Chairman Jerome Powell

- “We should be less fearful about inflation around the corner and recognize that that fear costs millions of jobs—millions of livelihoods, millions of hopes and dreams.” – Mary Daly, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

- “I’m not worried about inflation going up substantially beyond 2.5%. I don’t even fear 3%.” – Charles Evans, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

But as inflation continuously climbed, the tune changed:

“We’re experiencing a big uptick in inflation, bigger than many expected, bigger certainly than I expected. We’re trying to understand whether it’s something that will pass through fairly quickly or whether, in fact, we need to act.”

Jerome Powell, Fed Chairman, July 2021

During all this time, the Fed has ignored its own internal guidelines, which dictate that they raise rates immediately when inflation goes above 2%, and for over a year analysts have been stating that “the Fed is behind the curve.”

What is the Fed doing to fight inflation?

Though consumer prices have risen at the highest rate in over 40 years, the Fed hopes that inflation will decrease as the economy recovers from the pandemic. So far, it has raised the funds rate twice but is signaling that more raises are likely during the year.

What actions should the Fed take?

Economists and business leaders are conflicted about the future and what action the Fed should take. Some say that inflation will fall as supply chains normalize and demand tapers. Their concern is that the Fed will overreact, sending the economy into recession: “If the central bank doesn’t take its foot off the accelerator gradually now, it may have to slam on the brakes later,” risking either a recession or financial instability.

Others are content with higher inflation, pointing to its possible link with higher growth:

- “It is also useful to remember that too-low inflation is just as big a problem as too-high inflation.” – Christine Romer, professor of economics at the University of California, Berkeley

- “I don’t think it’s all going to be temporary, but that doesn’t matter if we have very strong growth.” — Jamie Dimon, chief executive of JPMorgan Chase

- “But if temporary inflation is a sign that we are headed back to a growing GDP with rising wages and plentiful jobs, what’s the scare in that?” – Austan Goolsbee, professor of economics at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business

Will the Fed be able to tame inflation?

Many observers question whether the Fed can effectively act to control inflation or guide the economy due to the unique combination of global and national forces in play today:

The costs of the Russia-Ukraine war

The conflict has divided the global community, potentially creating an irreversible rift between the East and West. Billions of dollars are being transferred to defense budgets, taking them away from supporting the global economy.

Energy prices are soaring

Due to the war, the supply of Russian oil and gas to European nations has been eliminated or drastically cut. As a result, global energy prices have escalated and will likely remain high for years until relations stabilize. The World Bank estimates that energy price increases will exceed 50% in 2022 and are unlikely to return to levels before the pandemic.

We are facing global food shortages

Russia and Ukraine supply a significant amount of the world’s grains (wheat, barley, maize) and oils (sunflower seeds). Food prices rose 31% in 2021 and 22.9% so far in 2022. The war in Ukraine is likely to significantly cut global food supplies, with far-reaching consequences such as hunger and food shortages worldwide.

Covid outbreaks threaten productivity

New variants of the coronavirus continue to emerge. Most of them are less deadly but more contagious and could idle a large part of the workforce. In the spring of 2022, China is facing its worst pandemic outbreak so far.

The purchasing power of the dollar is dropping

Despite the negative impact of inflation on the US population, I don’t believe that the Fed is likely to take aggressive action to cool the economy in the short term. Our money supply, a driver of inflation, will continue to grow with the need to fund the massive deficits from the war in addition to the costs of rebuilding the national infrastructure and maintaining the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

So, it looks like inflation is here to stay, the outlook on economic growth is unclear, and expectations of low unemployment either. What we have for sure is a continuous loss of purchasing power as the value of our dollar deteriorates. Strategies to preserve our purchasing power are what is now required.

The post The Federal Reserve Flirtation with Inflation appeared first on Gold Alliance.